Three Goal-Setting Framework Pitfalls

… and how to overcome them for game-changing results

Leaders don't fail at goal-setting because they pick the wrong framework. They fail because setting meaningful goals is deeply uncomfortable, leading to unconscious self-sabotage through busy work and counter-productive activities. Luckily, these patterns of behavior can be reprogrammed to deliver incredible results.

I know this because back in 2019, I tumbled down the OKR rabbit hole, enthusiastically adopting them as our company’s goal-setting framework. Right now you’re probably having one of three reactions:

“What is OKR? It sounds serious. Is it treatable?” (It’s a goal-setting approach called Objectives and Key Results used in business. Luckily, yes, there’s a cure. I made a full recovery!)

“What an idiot! OKRs are trash.” (I hear you, but stick with me for a few minutes.)

“I love OKRs!” (Just kidding. No one sane thinks this.)

In September 2019, I was the CEO of a technology consulting business where I had made dramatic changes over the previous twelve months. I was proud of what my team had achieved, but I knew more changes were needed for us to reach higher and more predictable levels of success. OKRs1 seemed like a good tool to continue that transformation.

The wide range of opinions on OKRs can be found in hot-take-filled posts like OKRs Are Bullshit and Stop Letting OKRs Masquerade as Strategy, to success stories like How Pinterest Uses OKRs To Achieve Stretch Goals. These mixed reactions aren’t unique to OKRs — you’ll find a wide range of reactions to every goal-setting framework: SMART, Balanced Scorecard, EOS, and Scaling Up all have ardent supporters and vocal detractors. I was skeptical that a framework alone would provide a quick fix to our challenges, but OKRs seemed like the best possible starting point.

After navigating many challenges with OKRs and talking to other leaders who have used similar frameworks, I’ve come to realize that they are often misused in counterproductive ways. Sometimes, this misuse is unintentional, as a poorly performed exercise can sometimes look and feel like it’s being done correctly based on how a goal was defined or implemented.

Other times, leaders’ egos are to blame. Setting the best business goals forces our egos to admit something unpleasant, like embarrassment from failure or uncertainty when others expect us to have answers. I’ve felt all of these feelings:

“My previous strategy failed.”

“The team I hand-picked and trusted to deliver isn’t performing, and it’s my fault.”

“This situation is dire and requires dramatic action.”

Delivering incredible results requires discomfort, and leaders’ egos can’t be excluded from this unpleasant-but-necessary byproduct of change. Every company and individual has their own idiosyncrasies, but my experiences have taught me that the challenges leaders face have many similarities. The discomforts arising from these challenges typically fall into one of three patterns:

1. The Productivity Illusion: Building systems rather than facing hard choices

“Should we get a product to help us track OKRs?”

This question was proposed soon after we finished the first draft of our new OKRs. On the surface, it seemed perfectly reasonable. I was tempted! “A software product probably would make this less painful,” I thought.

I even went deep into the weeds of looking at SaaS products for this purpose. And, I’ll admit — this brief diversion from the real task felt good. Ultimately, what I lacked in insight at that time was made up for by frugality and luck. Instead of an app, we made do with a Google Spreadsheet — a barebones approach that taught me a valuable lesson.

Implementing a new fancy-schmancy goal-tracking system or creating a flashy metric system can fool you into thinking you are making progress. The unfortunate reality is that these activities do not result in progress — they are the knowledge work equivalent of spending hours analyzing what new running shoes to buy instead of just going for a run.

The mentality adjustment needed to realize this is usually the real root of the problem and is more difficult to fix. If you or someone on your leadership team is reflexively finding excuses to delay work towards goals until/unless some other problem is fixed, it’s a form of professional procrastination. There is no way around this challenge, only through it. Open a Google sheet or Word document and start chipping away.

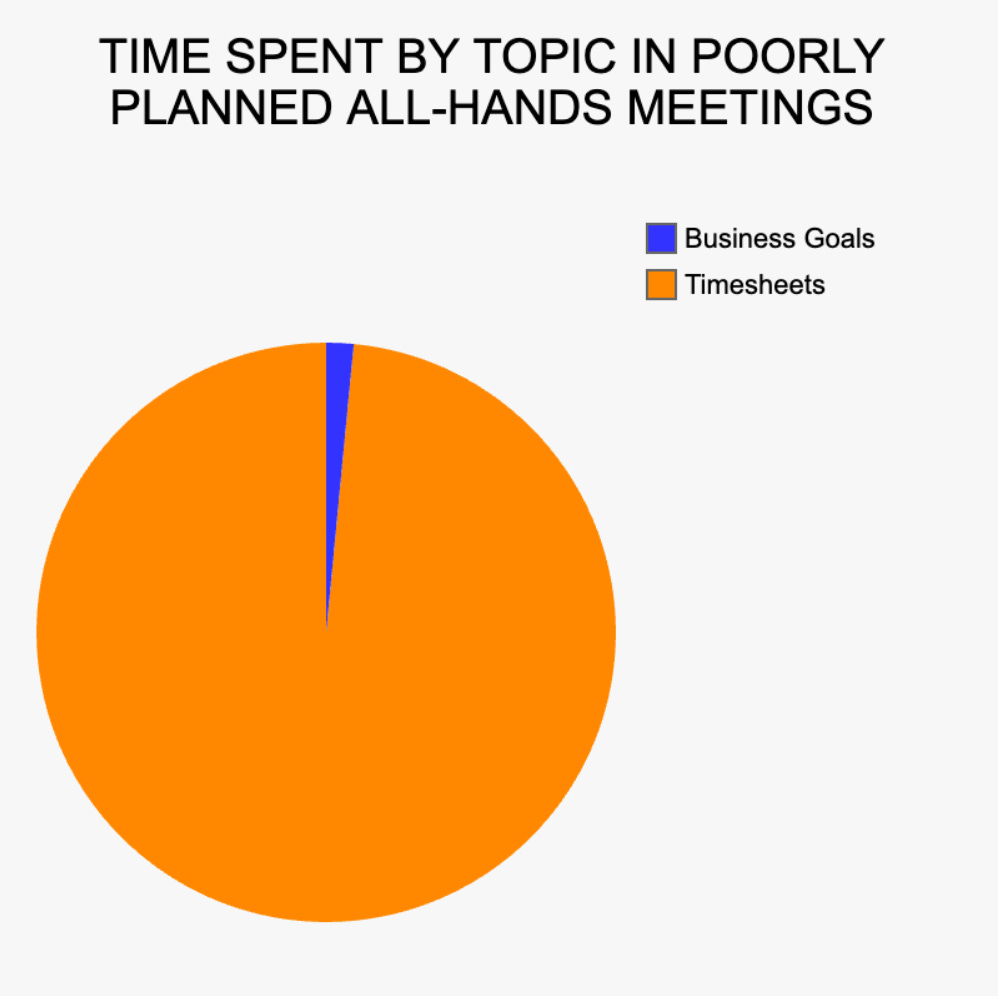

2. The Miscommunication Pattern: Team communication isn’t focused on goals

The calendar said it was time to plan our next quarterly all-hands meeting, but by my internal clock, the previous one felt like it was just yesterday. “People must be sick of hearing about this goal by now. Do we have enough interesting news about it to share an update?” I’d wonder.

The temptation to simply copy the agenda from the last meeting would often arise — it’s much easier to fill time with fluff than to craft a thoughtful message providing employees with what they need to know to achieve our collective goals. Instead of doing that hard work, it’s possible to fill some time and tick the box that an update was given, even if it was of no value.

Such a temptation might seem to stem from laziness, but there are often deeper root causes. Sometimes, the truth can be hard to verbalize. Explaining not just what the goals are but why they were chosen can be hard, especially if the goal-setting process itself didn’t start with leaders asking, “Why are we doing these specific things and not something else?”. And, if the organization isn’t yet attaining its goals, leaders may reflexively protect their egos by avoiding admitting failure or explaining a change in direction. As a result, the amount of time spent discussing goals is limited, or the substance is kept too superficial to be meaningful.

The antidote to this behavior is to use the temptation to “mail it in” when communicating about goals as a signal. The signal suggests that the message – or maybe the goals themselves – deserve deeper inspection. Sometimes, it’s hard for the individual responsible for delivering the message to spot the problem. Giving trusted leaders permission and encouragement to pressure test and critique communications about goals is a useful tactic to bring these problems to the surface.

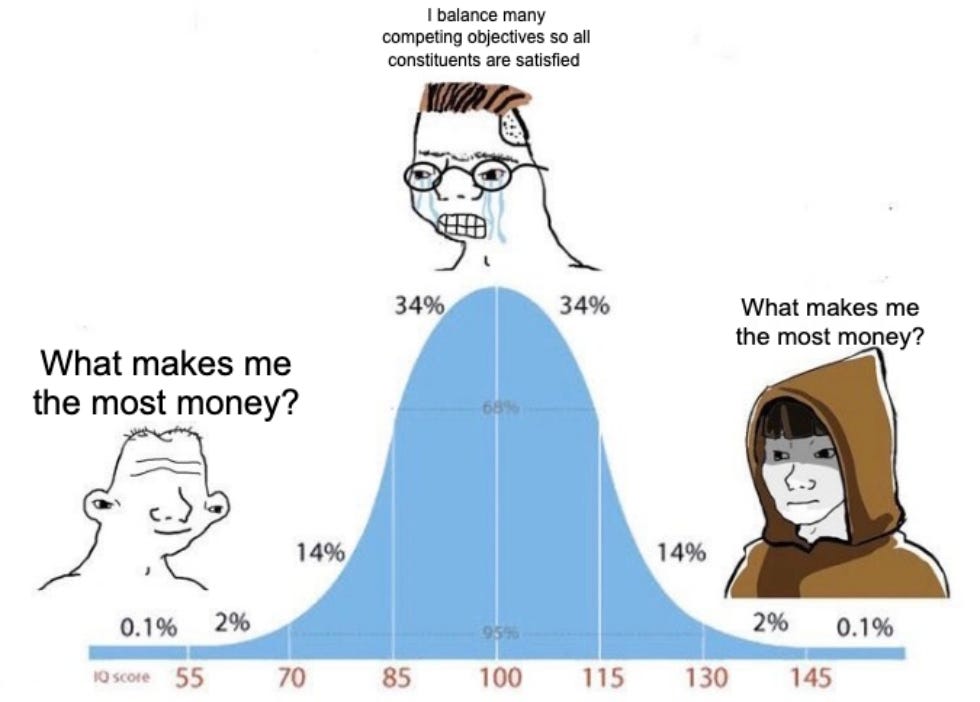

3. The Conflict Avoidance Pattern: Delaying hard conversations about money

One of our leaders and I were having a difficult conversation. “Our commission plans still aren’t right,” he said, clearly frustrated. I wish I could say that this came as a surprise, but it didn’t. “We need to adjust them to stop rewarding the wrong kinds of sales,” he concluded.

I didn’t want to hear this. Changing employees' variable compensation plans can be disruptive. If expectations haven’t been set appropriately, or if employees believe these changes are because the company is taking advantage of them, these changes can be demoralizing.

In my head, I was already thinking of ways to delay the pain. “Maybe we can wait until Q4 to make the adjustments as part of a bigger revamp of compensation, and we’ll have more time to message it,” I pondered.

This thought process isn’t unique to me or to commission plans: many leaders flinch at when they know they need to have a difficult conversation about a widespread, impactful change. But in the long-run, avoiding short-term pain only works against their – and their employees – long-term interest. If business conditions require rapid adjustments to commission plans or anything else, having upfront conversations as soon as possible is always the better option.

—

The uncomfortable truth is that no goal-setting framework will save you from self-defeating psychological traps like those above. My awareness of these traps grew only through a combination of trial-and-error and leadership coaching — the fact that I call my coach my “work therapist” is only partially a joke!

Awareness of the patterns of failures and a willingness to confront them is the antidote to these self-defeating behaviors. As leaders working with a goal-setting system, we need to ask ourselves:

What hard conversation am I avoiding by focusing on processes instead of outcomes?

Do we have the appropriate style, frequency, and substance of communication about our goals and progress?

What conversation am I avoiding, and what am I delaying or giving up as a result?

Goals are like exercise: if the process doesn’t challenge you, you’re probably doing it wrong. You don’t have to get it all right on the first try. Creating and managing ambitious goals at least a little bit wrong allows you to gather information and figure out how to course-correct. The only way to achieve the desired results is to be aware of the possible pitfalls along the way and adjust when you inevitably begin to fall into one of them.

The first year of my OKR experiment was rocky, but the goal-setting process continues to improve with experience. There is no way to get to the improvements made in year two without embracing the discomfort of year one. Just start.

—

Thanks to Tahsin Khan, Amit Bhatia, Lily, Rick Lewis, Larry Urish, and Emily Ann Hill for their feedback on earlier drafts of this post and to Sandhya Doma and Lily for sharing their experiences with goal-setting frameworks that helped shape my approach to this topic. Also, many thanks to my old leadership team and the “work therapist” I mentioned above, without whom I wouldn’t have learned all these lessons. :-)

Objectives and Key Results, or OKRs, weren’t new. The approach was first used by leadership at Intel in the 1970s, and it enjoyed a resurgence in popularity around 2018 because of its use at Google. This combination inspired John Doerr’s book “Measure What Matters” and consequently resulted in many CEOs like me embracing the approach at the time.

The premise of OKRs, like most goal-setting frameworks used in business, is simple: identify a small number of objectives for the company. For each objective, identify the key results that, if all were satisfied, would mean the objective must have been achieved. Each key result should be measurable and time-bound. Key results have no grey area. They’ve either been achieved, or they haven’t.

Happy to see this polished and published!

"What hard conversation am I avoiding by focusing on processes instead of outcomes?"

We can also substitute "conversation" with "decision" and find that we're falling into the same trap there as well. Avoiding difficult conversations/decisions and distracting ourselves with "optimizing processes"...I fall into this trap every day lol

"There is no way to get to the improvements made in year two without embracing the discomfort of year one. Just start." This is a great reminder for everything in life.