Sales Commission Plans for Professional Services Companies with Dedicated Sales Teams

Building an effective sales function is critical to the success of professional services companies. Doing so requires answering three key questions:

What type of sales model is appropriate for the services being offered?

Are you using a “seller/doer” or dedicated salesperson(s) within that sales model?

How do you compensate the people selling?

I wrote about picking sales models and services offerings a few weeks ago. For today’s post, I’m focusing on cases where “direct sales” is the answer to question 1.

Let’s consider questions 2 and 3 to set up some critical context for the rest of the post.

The evolution of sales in a services company

The sales function typically goes through stages as a company grows and matures:

It usually starts with a founder doing all of the selling using her network. At some point, the company reaches the point where having someone dedicated to selling is needed to continue growing at the same (or faster) rate.

Question 2 determines which fork in the road is taken: is it better to have a dedicated seller/doer or a dedicated salesperson?

A seller/doer remains involved in delivering work - usually in a billable capacity - while also selling.

This can work well with high-touch, strategic- or management-consulting style engagements. It also works well when the relationship with the client is expected to be long-term (i.e., multiple years). The seller/doer typically has a high degree of expertise in delivering the work and is usually involved with only one, or at most two or three, clients at once.

A dedicated salesperson is focused on account and relationship management. They do not participate in delivering the services at all. As a result, they usually need to involve someone from a delivery team in defining and scoping engagements. A dedicated salesperson is dedicated to selling, but not necessarily to a single client or prospect. A dedicated salesperson can interact with more clients and prospects than a seller/doer.

For today’s post, I will focus on this dedicated sales approach because it’s the one that most often requires sales commission plans. It can be helpful to see the implications of this path before you get to the “at scale” version, too.

Sales commission plans

One component of this is creating a sales commission plan that encourages the desired behavior of salespeople.

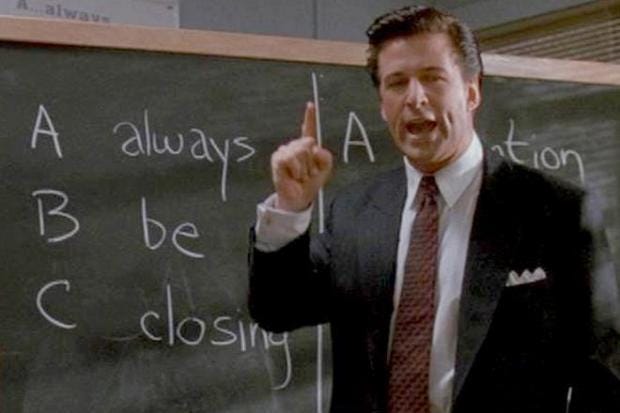

Of course, all good salespeople want to sell. Encouraging the desired behavior means focusing on the right kinds of opportunities for the business. It is also one of the hardest things to get right.

All sales commission plans run the risk of unintended consequences. The second-order effects of a seemingly simple decision can be hard to predict. For example, suppose there is no way to “make up” a quota miss in a previous quarter in a future quarter.

In that case, a salesperson may sub-optimize an opportunity that is close to closing to get it to close in the quarter, even if spending a couple more days might lead to a more significant deal that is better for the business. Sub-optimizing could mean reducing rates to speed up approval by the prospect, shortening the length of an engagement, or cutting corners on scoping.

As services companies grow into hundreds or thousands of employees, sales commission plans may, by necessity, become more complicated. Today I will focus on building good commission plans for smaller businesses.

Creating good commission plans

Good sales commission plans echo the top-level business objectives and strategy, particularly concerning revenue growth and profitability targets. If these objectives aren’t well-defined, sales commission plans are quickly muddied.

Bad commission plans often include lots of different levers or variables and are hard to administer because the underlying data to calculate commissions is hard to get, and the calculations are burdensome.

In a typical dedicated sales commission model, 30-50% of a salesperson’s compensation will be from commission. Think about the “on target earnings” (OTE) of a salesperson who meets their quota. Whatever that number can be decomposed into these three components:

Commission on revenue

Approximately 30-40% of the overall commission should be based on invoiced (i.e., recognizable) revenue.

Commission plans that reward bookings rather than revenue may incentivize selling large deals that may never generate the total value of the booking. This can create a significant cash flow burden on the business because commission payments must be made without the receivables to fund it.

Commission on project margin

Another 30-40% of the commission should be based on achieving a project gross margin target. This component can be scaled where more commission is earned as the margin increases. For example, a higher commission percentage might be paid above a percentage of realized project margin. Similarly, the commission earned would decrease if the realized project margin decreased.

This aligns the salesperson's interests to maximize the profitability of the business. Without this being a significant component of their commission, a salesperson may be tempted to sell projects at a lower (or zero!) gross margin because it's easier to win business, and there is no penalty for doing so.

The key to calculating this margin component is to have reliable, repeatable data on realized project margin that can be tied back to the opportunity the salesperson sold. This can be harder than it sounds! If you aren’t already producing monthly reporting on actual project margin, ensure you can create that report before introducing this commission component. (I've written about pricing projects and estimating labor costs before.)

Commission based on quota attainment

The remaining percentage of the commission should be based on achieving quarterly quota targets. The quota target should be a stretch goal that is difficult but attainable. If every salesperson is hitting their quota every quarter, your quotas need to be higher! Aim for 60-80% of salespeople to make their quotas.

Commission plans should allow for a trailing quarter quota recovery. A salesperson who misses their quota in one quarter can recover that quota attainment commission if they exceed it the next quarter. For example, if the quota wasn’t met in Q1, but in Q2, a salesperson crushes it and exceeds their Q2 quota (achieving their Q2 quota and completely making up for the shortfall in Q1), they would get their Q1 and Q2 quota attainment commission.

The leadership of the business can consider extending this quota recovery benefit to any quarter within the fiscal year. This gives more flexibility to the salesperson, and, as a small, private company, quarterly targets may be less critical than yearly targets.

In this scenario, a salesperson could, for example, narrowly miss their Q1 and Q2 quota, meet their Q3 quota, and in Q4 close a monster sale. The Q4 win achieves their Q4 quota and makes up for the shortfall in their Q1 and Q2 quotas. As a result, they would be paid quota attainment for all four quarters.

Doing this prevents destructive behaviors like selling a smaller deal in the current quarter because it’s easier to close than spending more time and having it slip to the next quarter. It also rewards good behaviors, allowing a salesperson who legitimately had a lousy quarter to dig themselves out through high performance.

Other commission plan considerations

There are a couple of other things that should be included in commission plans - subject to the laws in the jurisdiction they’re being used in - to protect the business and salespeople:

Reserve the right to change commission plans at any time

The provision to change a commission plan should be invoked rarely and only when it is essential to address a critical problem with the business (e.g., severe financial distress that could be business-ending) or an unintended consequence of the plan that is unfavorable to the salesperson.

Sales personnel should have confidence that the ground won’t move underneath their feet unless it’s really important for business success. If leadership needs to make an off-schedule change to commission plans, it should be coupled with good communication explaining why it’s necessary.

Commission plans terminate immediately upon the termination of employment

This creates clarity for both parties about what happens if a salesperson’s job is terminated. Commission agreements should be clear about when a commission is considered “earned” because all earned commissions must be paid to a terminated employee.

Some states in the US also have employment laws that require the payment of commissions to terminated employees on a particular schedule - sometimes much faster than a normal payroll cycle. It’s always a good practice to have an employment lawyer review commission agreements and ensure that the business is operationally prepared to comply with local law.

Grandfather legacy commission agreements for fairness

Changing commission plans always creates stress for salespeople. Business needs and evolving business conditions also generate pressure on leadership. It’s essential to be fair to both parties. If a change to a commission plan significantly disadvantages or demoralizes a salesperson, it’s terrible for both the salesperson and the business. One way to rectify this is to grandfather some legacy commission plans for specific accounts, opportunities, or a transitional period.

Putting commission plans into action

I’ve covered the key components of what goes into a commission plan. Now what?

Rolling out a commission plan will go more smoothly with the following planning:

Work with a lawyer to draft a commission plan agreement template addressing the above points. Key numbers that may change, like the commission rates on revenue, margin, and quota attainment, should be highlighted so you can adjust them as you model different variables in the plan.

Model different scenarios for each salesperson to see how much commission would be paid in a worst-case, average-case, and best-case year. It’s helpful to have a spreadsheet-driven model where you can plug in the variables of revenue and average project margin by quarter and see how that affects commissions.

Consider it through both the company’s lens (“is this in line with our budget for SG&A expense?” and “will we have the cash to pay this when it’s earned?”) and the salesperson’s lens (“is this fair compensation for performance and in line with OTE expectations?”).Test the business’ ability to report on the sales and invoicing data necessary to calculate commissions. One good way to do a “dry run” is to try to generate a spreadsheet with sales commission calculations for the previous quarter before rolling out the plans. Does all the data exist in CRM systems, invoices, etc.? Is the process repeatable every quarter?

Communicate with the affected salesperson(s). Like any change to compensation, this may have legal implications depending on the company’s existing employment agreements and where the company operates. Beyond being legal, it should be seen as a “win/win” by both parties: motivation for the salesperson to perform and motivating for the company to support the salesperson's success.

✌🏼 That’s it for this week. What have you seen work - or not work - in commission plans?