Empty calorie innovation is a bad corporate diet

Why do big companies fail at innovation?

They fail because they prioritize unambitious projects in a misguided effort to achieve scale. Inside those companies, hiding amongst Excel spreadsheets and bureaucratic processes, are the ingredients for innovation.

The ingredients don’t appear on a balance sheet or org chart. They are abstract: ideas, passion, change. Willingness to challenge the status quo. All critical precursors to a great finished product, but too often they remain abstract – it takes a specific type of hard work to make them concrete.

I confess to being an accomplice to some failed innovation attempts. I’ve helped administer the rigid processes that select poor ideas and dutifully led their implementation. I’ve watched teams with tremendous ideas and technical potential squelched by unimaginative executives. I’ve witnessed the slow burn of talented, committed people who have toiled on unambitious projects for years, ultimately failing to transform an industry. And, most embarrassingly, I ate some “empty calorie” innovation meals – while the projects that created them spiraled to their eventual failure.

But we also have a front row seat to the frontiers of ambition: SpaceX catching a 440,000 pound rocket from 131 miles above Earth, Google creating self-driving cars with Waymo, Microsoft reinventing itself as a public cloud company and AI leader with Azure and its OpenAI partnership.

Innovation can happen anywhere, but it never happens overnight. SpaceX is now a 22 year old startup. Waymo was conceived around 2008, when Barack Obama first took office. Microsoft’s transformation under chief Satya Nadella has been ten years in the making. Setbacks happened routinely. It’s easy to overestimate the speed of success. It's only in hindsight that people claim to have known that an ambitious idea was destined to succeed.

Innovation doesn’t need to be flashy to make an impact. Breakthroughs are often only visible beneath the surface, invisible to all except industry insiders. As an example, data scientists created new algorithms that optimized the storage and distribution of food from warehouses, enabling adaptations to rapidly changing purchasing patterns. At the height of the COVID pandemic, these innovations prevented much more severe food shortages. If you’re thinking, “this doesn’t sound that cool,” you just proved my point!

Not all attempts at innovation are created equal. Their relative inequality can be viewed through two lenses, ambition and scale. Distilling innovation into a simplistic framework allows direct, honest comparison of otherwise unrelated ideas.

Ambition is hard to quantify, but developing an efficient, reusable spacecraft with a 20-fold reduction in cost, is clearly on one end of the spectrum. At the opposite end is a team adding a product feature their competitor already has to their mobile app.

Scale can be measured by two instructive metrics: how many people will use the thing and how much revenue or profit it will create. Crucially, scale can change over time – an important feature of innovation that we will revisit.

The universe of innovation efforts can be distilled into a two-dimensional view, plotting their ambitiousness (how crazy the idea seems) on one axis and their scale (# of customers, $ impact) on the other:

Like every two-by-two grid created by a consultant (guilty as charged!), the upper right quadrant is the sweet spot. The challenge is the path to get there.

The companies that earnestly attempt to innovate but fail often come up short because they worry too much – and too soon – about scale and undershoot the ambition of the improvement. An easy trap to get caught in.

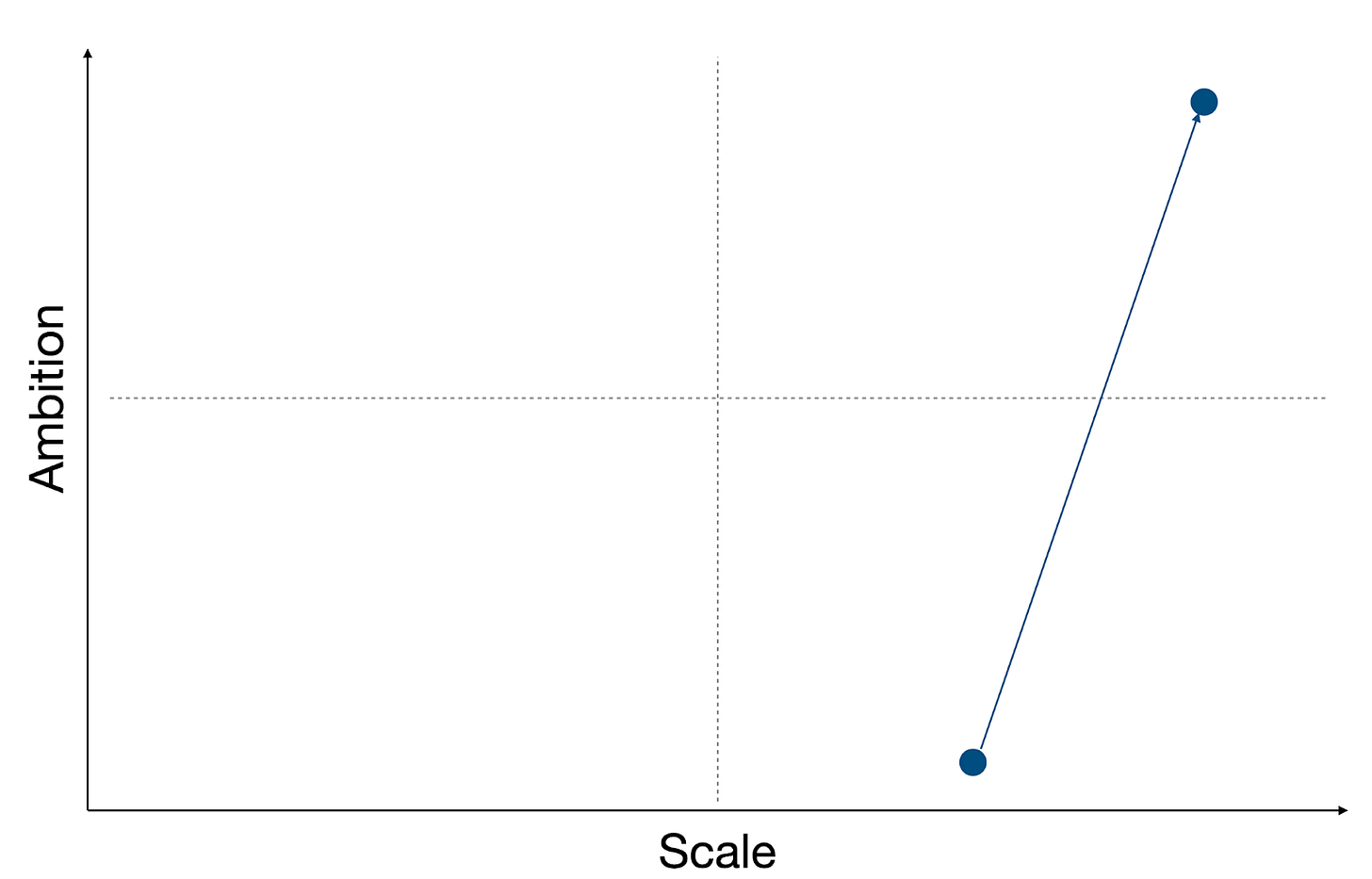

The companies lionized for innovation have trajectories like this:

They start with little-to-no scale. Many began with zero customers. Even if the company had scale with other products, they iterated on a new product and figured out how to scale it later. Experienced innovators know this can take years!

However, big companies fail when they are too accustomed to scale. Product teams improve their wares through iteration that is too incremental. When applied to innovation, the iteration muscle memory kicks in. Aspirationally, it looks like this:

But when the expected innovation never happens, or if the idea wasn’t innovative in the first place, reality looks like this:

This might be fine if the goal was to generate a little revenue or add a feature. Let’s be honest and call it what it is: an iteration, not a grandiose idea.

Best case scenario, this is still accretive to a company’s profit. Most often, the product is filler material in an innovation team’s portfolio so they can declare success and move on. The worst case scenario though, is disastrous. Losing hundreds to billions of dollars while delivering little to no benefit to customers.

In starting with scale, most “innovation” is really a new feature bolted on to an existing product. Framing the work as innovative, rather than just good product management, sets the bar artificially high.

This is why I call it “empty calorie” innovation — it seems desirable when you order (design) it, tastes good when you eat (launch) it, but it provides none of the nutrients to the organization as succeeding with something truly ambitious.

So if this is why big companies fail at innovation, how can they do better?

For early stage startups, Paul Graham’s excellent essay “Do Things that Don’t Scale” is a well-known treatise, widely regarded as the gospel for creating valuable products from scratch. His ideas are no longer controversial for young companies because they’ve been proven to work. To larger companies, his ideas like performing manual tasks first, automating later, or working one-on-one with early prospective customers, are still anathema.

I am proposing an application of “do things that don’t scale” for big companies: Innovation efforts should start from a truly ambitious idea. There is no shortcut to achieving scale, and it is very rare that a simple idea evolves into something transformational. Instead of trying to “cheat scale” by building scaffolding, start with ambition and figure out how to scale later.

One objection to this approach is that public companies have a structural constraint: the quarterly earnings cycle. That’s a cop out – for many companies, pleading with Wall Street is a prison of their own making. It’s no coincidence that the most innovative public companies have conditioned their investors to expect longer return cycles on strategic investment. Amazon, Apple, Google/Alphabet, and Meta all buck the myopic trend of earnings being delivered from short-term investments. Public companies need more air cover from CEOs and investor relations teams to set expectations of long-term investment for ambitious projects.

While private companies aren’t accountable to the public markets, they often have boards or investors with similar attitudes. Finance teams too easily convince themselves that the time to achieve ROI is too long or the IRR is too low in a spreadsheet model. Excel is a wonderful tool when used responsibly, but the spreadsheet is where ambition goes to die. Remember, models are just models. The risks posed by failing to innovate are real, and history is littered with “successful” companies that were made extinct by more imaginative competitors. (All those dead companies had Excel models, too!)

Ambition doesn’t have to be expensive. Starting without scale actually means lower initial costs in operations and support. If cost is the only reason a project can’t get started, look for the hidden assumptions about scale that are wrong.

Empty calorie innovation is a bad corporate diet, and the leadership of those companies can do better. Many of the obstacles to better innovation can be addressed by starting from ambition rather than scale. Conveniently, eliminating scale as a requirement for approving an innovation effort often makes the financial investment more palatable. Every successful innovation I’ve worked on had these characteristics at the beginning. In the kitchen of innovation, the best meals begin with good ingredients and the idea for an ambitious dish – not worrying about how big your dining room is.

Real innovation tastes better, and a better corporate diet is good for everyone!